Portal:Jupiter

Submillimeters

The map at right "shows the distribution of water in the stratosphere of Jupiter as measured with the Herschel space observatory. White and cyan indicate highest concentration of water, and blue indicates lesser amounts. The map has been superimposed over an image of Jupiter taken at visible wavelengths with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope."[1]

"The distribution of water clearly shows an asymmetric distribution across the planet: water is more abundant in the southern hemisphere. Based on this and other clues collected with Herschel, astronomers have established that at least 95 percent of the water currently present in Jupiter's stratosphere was supplied by comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, which famously impacted the planet at intermediate southern latitudes in 1994."[1]

"The map is based on spectrometric data collected with the Photodetecting Array Camera and Spectrometer (PACS) instrument on board Herschel around 66.4 microns, a wavelength that corresponds to one of water's many spectral signatures."[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 T. Cavali (23 April 2013). Distribution of Water in Jupiter's Stratosphere. ESA/Herschel/NASA. http://www.herschel.caltech.edu/image/nhsc2013-014a. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

Object astronomy

"[T]he ancients’ religions and mythology speak for their knowledge of Uranus; the dynasty of gods had Uranus followed by Saturn, and the latter by Jupiter."[1]

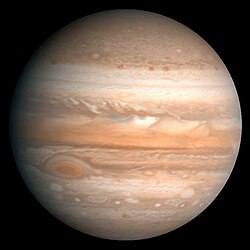

"This false-color view of Jupiter [on the right] was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2006. The red color traces high-altitude haze blankets in the polar regions, equatorial zone, the Great Red Spot, and a second red spot below and to the left of its larger cousin. The smaller red spot is approximately as wide as Earth."[2]

"NASA's Hubble Space Telescope is giving astronomers their most detailed view yet of a second red spot emerging on Jupiter. For the first time in history, astronomers have witnessed the birth of a new red spot on the giant planet, which is located half a billion miles away. The storm is roughly one-half the diameter of its bigger and legendary cousin, the Great Red Spot. Researchers suggest that the new spot may be related to a possible major climate change in Jupiter's atmosphere. These images were taken with Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys on April 8 and 16, 2006."[2]

References

- ↑ Immanuel Velikovsky. Uranus. The Immanuel Velikovsky Archive. http://www.varchive.org/itb/uranus.htm#f_1. Retrieved 2013-01-14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 I. de Pater and M. Wong (4 May 2006). Hubble Snaps Baby Pictures of Jupiter's "Red Spot Jr.". Baltimore, Maryland USA: HubbleSite. http://hubblesite.org/news_release/news/2006-19/20-jupiter. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

Jupiter systems

Center is a Voyager 2 image of Jupiter's rings.

Marduk

~2800 b2k: The observation of Jupiter dates back to the Babylonian astronomers of the 7th or 8th century BC.[2] To the Babylonians, this object represented their god Marduk. They used the roughly 12-year orbit of this planet along the ecliptic to define the constellations of their zodiac.[3][4]

Marduk Sumerian: amar utu.k "calf of the sun; solar calf"; Greek Μαρδοχαῖος,[5]

"Marduk" is the Babylonian form of his name.[6]

The name Marduk was probably pronounced Marutuk.[7] The etymology of the name Marduk is conjectured as derived from amar-Utu ("bull calf of the sun god Utu").[6] The origin of Marduk's name may reflect an earlier genealogy, or have had cultural ties to the ancient city of Sippar (whose god was Utu, the sun god), dating back to the third millennium BC.[8]

By the Hammurabi period, Marduk had become astrologically associated with the planet Jupiter.[9]

Marduk's original character is obscure but he was later associated with water, vegetation, judgment, and magic.[10] His consort was the goddess Sarpanit.[11] He was also regarded as the son of Ea[12] (Sumerian Enki) and Damgalnuna (Damkina)[13] and the heir of Anu, but whatever special traits Marduk may have had were overshadowed by the political development through which the Euphrates valley passed and which led to people of the time imbuing him with traits belonging to gods who in an earlier period were recognized as the heads of the pantheon.[14]

Leonard W. King in The Seven Tablets of Creation (1902) included fragments of god lists which he considered essential for the reconstruction of the meaning of Marduk's name. Franz Bohl in his 1936 study of the fifty names also referred to King's list. Richard Litke (1958) noticed a similarity between Marduk's names in the An:Anum list and those of the Enuma elish, albeit in a different arrangement.

The connection between the An:Anum list and the list in Enuma Elish were established by Walther Sommerfeld (1982), who used the correspondence to argue for a Kassite period composition date of the Enuma elish, although the direct derivation of the Enuma elish list from the An:Anum one was disputed in a review by Wilfred Lambert (1984).[15]

Marduk prophesies that he will return once more to Babylon to a messianic new king, who will bring salvation to the city and who will wreak a terrible revenge on the Elamites. This king is understood to be Nebuchadnezzar I (Nabu-kudurri-uṣur I), 1125-1103 BC.[16]

References

- ↑ Willis, Roy (2012). World Mythology. New York: Metro Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4351-4173-5.

- ↑ A. Sachs (May 2, 1974). "Babylonian Observational Astronomy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (Royal Society of London) 276 (1257): 43–50 (see p. 44). doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0008.

- ↑ Eric Burgess (1982). By Jupiter: Odysseys to a Giant. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-05176-X.

- ↑ Rogers, J. H. (1998). "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 108: 9–28.

- ↑ identified with Marduk by Heinrich Zimmeren (1862-1931), Stade's Zeitschrift 11, p. 161.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Helmer Ringgren, (1974) Religions of The Ancient Near East, Translated by John Sturdy, The Westminster Press, p. 66.

- ↑ Frymer-Kensky, Tikva (2005). Jones, Lindsay. ed. Marduk. Encyclopedia of religion. 8 (2 ed.). New York. pp. 5702–5703. ISBN 0-02-865741-1.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Religion - Macmillan Library Reference USA - Vol. 9 - Page 201

- ↑ Jastrow, Jr., Morris (1911). Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria, G.P. Putnam's Sons: New York and London. pp. 217-219.

- ↑ [John L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible, Simon & Schuster, 1965 p 541.]

- ↑ Helmer Ringgren, (1974) Religions of The Ancient Near East, Translated by John Sturdy, The Westminster Press, p. 67.

- ↑ Arendzen, John (1908). Cosmogony, In: The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04405c.htm. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ↑ C. Scott Littleton (2005). Gods, Goddesses and Mythology, Volume 6. Marshall Cavendish. p. 829.

- ↑ Morris Jastrow (1911). Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria. G. P. Putnam’s Sons. p. 38.

- ↑ Andrea Seri, The Fifty Names of Marduk in Enuma elis, Journal of the American Oriental Society 126.4 (2006)

- ↑ Matthew Neujahr (2006). "Royal Ideology and Utopian Futures in the Akkadian Ex Eventu Prophecies". In Ehud Ben Zvi. Utopia and Dystopia in Prophetic Literature. Helsinki: The Finnish Exegetical Society, University of Helsinki. pp. 41–54.

External links

Jupiter appears in pastel colors in this photo because the observation was taken in near-infrared light. Credit: NASA, ESA, and E. Karkoschka (University of Arizona).

Blue vortex

This image shows distorted bands of clouds near the blue vortex on Jupiter captured by the Juno spacecraft.

Ganymede

"If Ganymede rotated around the Sun rather than around Jupiter, it would be classified as a planet."[1]

The Galilean Moons is a "name given to Jupiter's four largest moons, Io, Europa, Callisto & Ganymede. They were discovered independently by Galileo Galilei and Simon Marius."[2]

"Ganymede has a very distinct surface with bright and dark regions. The surface includes mountains, valleys, craters and lava flows. The darker regions are more heavily littered with craters implying that those regions are older. The largest dark region is named Galileo Regio and is almost 2000 miles [3200 km] in diameter. The lighter regions display extensive series of troughs and ridges, thought to be a result of tectonic movement."[1]

"A notable attribute of the craters on Ganymede is that they are not very deep and don’t have mountains around the edges of them as can normally be seen around craters on other moons and planets. The reason for this is that the crust of Ganymede is relatively soft and over a geological time frame has flattened out the extreme elevation changes."[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bjorn Jonsson and Steve Albers (October 17, 2000). Ganymede (Jupiter moon). NOAA. http://sos.noaa.gov/Datasets/dataset.php?id=247. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ↑ Aravind V R (April 17, 2012). Astronomy glossary. http://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Astronomy_glossary. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

Jupiter systems

"A definite color gradient is observed [in the small inner satellites of Jupiter], with the satellites closer to Jupiter being redder: the mean violet/green ratio (0.42/0.56 μm) decreases from Thebe to Metis. This ratio also is lower for the trailing sides of Thebe and Amalthea than for their leading sides."[1]

References

- ↑ P.C. Thomas, J.A. Burns, L. Rossier, D. Simonelli, J. Veverka, C.R. Chapman, K. Klaasen, T.V. Johnson, M.J.S. Belton, Galileo Solid State Imaging Team (September 1998). "The Small Inner Satellites of Jupiter". Icarus 135 (1): 360-71. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.5976. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103598959760. Retrieved 2012-06-01.